Vandergriff Analysis of "the Problem with Traditional 'Battle Drills'" by Warfare Mastery Institute (a department of the Special Tactics University)

His [Pete Hegseth] emphasis on wargaming and free-play scenarios over lane training is a nod to a 3GW culture. Yet, the institution resists. Why?

Vandergriff analysis of Article:

An Analysis of “The Problem with Traditional ‘Battle Drills’”

By Donald E. Vandergriff, Major, U.S. Army (Ret.) Author of Raising the Bar: Creating and Nurturing Adaptability to Deal with the Changing Face of War and Maneuver Warfare Handbook (in collaboration with William S. Lind)

The Warfare Mastery Institute’s recent piece, “The Problem with Traditional ‘Battle Drills,’” hits at the heart of a persistent cancer in American military culture: the rigid, formulaic application of tactics that masquerades as doctrine but delivers predictability and defeat.

Drawing from the forthcoming Small Unit Infantry Rural Combat serial, the authors rightly dismantle the “suppress and flank” drill, exposing its vulnerabilities in engagement distances, ammunition sustainment, exposure to unseen threats, enemy countermeasures, indirect fires, and directional inflexibility.

These are not mere quibbles with a single tactic; they reveal a deeper institutional failure to transition from Second Generation Warfare (2GW)—the attrition-based, centralized, process-oriented model born in the trenches of World War I—to Third Generation Warfare (3GW), the maneuverist paradigm pioneered by the German Blitzkrieg and refined in works like William S. Lind’s Maneuver Warfare Handbook.

Worse, this inertia leaves us ill-prepared for Fourth Generation Warfare (4GW), where non-state actors exploit our predictability in asymmetric, decentralized conflicts.

The article’s core insight—that battle drills are meant as temporary expedients to seize initiative while leaders assess and adapt—is spot-on, yet it underscores why they fail in practice. Manuals proclaim flexibility, but training and culture enforce rigidity. This is classic 2GW thinking: inward-focused, synchronization-obsessed, and reliant on top-down orders.

In 2GW, success comes from massing fires and following the script, as if war were an industrial assembly line. But as Lind and I have argued since the 1980s, 3GW demands Schwerpunkt (focal point), speed, surprise, and decentralized decision-making through Auftragstaktik—mission command—where subordinates act on intent, not checklists.

Consider the problems enumerated:

Engagement Distance and Ammo Load: A 500m flank under fire depletes machine guns before the assault begins. This assumes a static enemy and unlimited sustainment—hallmarks of 2GW attrition. In 3GW, we’d bypass such distances via infiltration or combined arms to create gaps, not grind through them. Lind’s analysis of Boyd’s OODA loop emphasizes getting inside the enemy’s decision cycle; a rigid flank lets the foe observe, orient, and counter before you decide or act.

Exposure to New Threats and Isolation: The flanking element uncovers unseen foes without support. This isolation stems from centralized control: the support element can’t adapt because it’s scripted to suppress, not observe or maneuver. Mission command empowers junior leaders to reconnoiter by fire or adjust on the fly, turning potential isolation into opportunistic envelopment.

Unpredictable Enemy Reaction: Assuming suppression pins the enemy ignores friction and initiative. 3GW thrives on enemy mistakes; we induce them through ambiguity, not predictable flanks. In 4GW, insurgents like those in Iraq or Afghanistan would exploit this by melting away, counter-flanking, or ambushing—precisely because our drills telegraph intent.

Enemy Indirect Fire: Prolonged static positions invite mortars. 2GW loves fixed firebases; 3GW disperses and moves fluidly, using tempo to deny targeting time.

Attacks from Other Directions: Overemphasis on frontal drills breeds directional bias. True 3GW is orientation-agnostic, with units trained in free-play exercises to adapt to any vector.

These flaws aren’t doctrinal oversights; they’re cultural. The Department of Defense—still clinging to its outdated “Department of War” ethos despite Secretary Pete Hegseth’s promising reforms—has made strides:

Hegseth’s push for outcomes-based training, leader development over PowerPoint, and decentralization echoes our calls in Path to Victory for adaptive, mission-type orders.

His emphasis on wargaming and free-play scenarios over lane training is a nod to 3GW.

Yet, the institution resists.

Why?

Bureaucratic inertia, risk-aversion, and a promotion system rewarding compliance over boldness. Hegseth’s initiatives—reviving the Army’s Maneuver Captain’s Career Course elements and piloting mission command in select units—are great starts, but they’re grafted onto a 2GW chassis. Without purging zero-defects culture and centralized evaluation, they wither.

To win in 3GW, we must institutionalize Auftragstaktik: clear commander’s intent, implicit communication, and trust in subordinates. Lind and I advocate tactical decision games (TDGs), sand tables, and force-on-force exercises where failure teaches. No more “crawl-walk-run” checklists; start with chaos to build intuition. For 4GW, this evolves further: small units as self-contained systems, blending maneuver with cultural acuity to out-think stateless foes who fight without fronts.

The Institute’s “Battlecraft” alternative is intriguing—a craft implying artistry over algorithm. It aligns with our vision: tactics as adaptable principles, not drills. Teach heuristics: find gaps, exploit tempo, combine arms implicitly. Ditch diagrams for scenarios where leaders deviate early.

Hegseth’s reforms could catalyze this shift, but only if we demand cultural revolution: promote maneuverists, reward initiative, and accept that 2GW won the last century’s wars but loses today’s. Until then, battle drills remain a crutch for a crippled doctrine. The Warfare Mastery Institute challenges us to walk unaided—into 3GW and beyond. Let’s heed the call.

For further reading: William S. Lind’s “Maneuver Warfare Handbook” and my “Adopting Mission Command: Developing Leaders for a Superior Command Culture.” Comments welcome; let’s discuss in the chat.

Begin Warfare Mastery Institute (of Special Tactics University) article:

The Problem with Traditional “Battle Drills”

Battle drills are misunderstood and misapplied, but is there a better way?

Oct 19, 2025

This article is drawn from our Small Unit Infantry Rural Combat book which we plan to publish here on Substack in serial form. It covers the problems with executing the classic “suppress and flank battle drill” in a rigid, formulaic manner. We welcome your reactions, comments and constructive criticism in the chat.

The Problem with “Suppress and Flank”

Over recent years the U.S. Army has changed it’s philosophy on “battle drills” several times but there remains a core problem that is difficult for mere doctrinal changes to correct. The problem is that battle drills are often misunderstood, mis-taught and misapplied. The key first point that is clearly written in most manuals but is often completely ignored is that battle drills are not intended as a rigid prescription that must be followed to the letter. Battle drills are a guideline or start point upon which to build and adjust your tactics based on the situation.

The second, often misunderstood logic of battle drills is that they are primarily designed to buy time for leaders to make a better, more flexible decision based on the situation. The idea behind a battle drill is that it gives the unit something to execute (or begin executing) right away in order to retain the initiative and keep the enemy off balance while the leader gathers information, assesses the situation and comes up with a better course of action.

Unfortunately, the way battle drills are described in manuals and taught in schools tends to cause leaders to forget the two points above and drift back into a rigid, process-based execution that looks exactly like the diagram in the manual. Attempting to fight in this way can lead to disastrous results in real combat. The rest of this article will explain why.

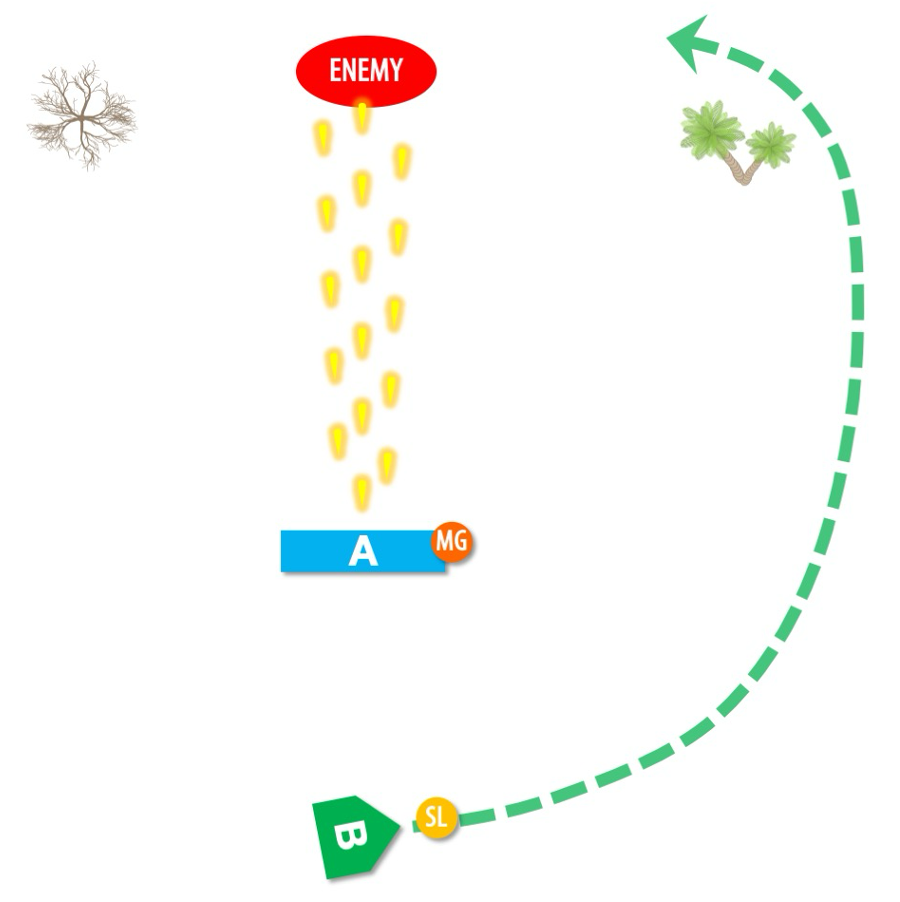

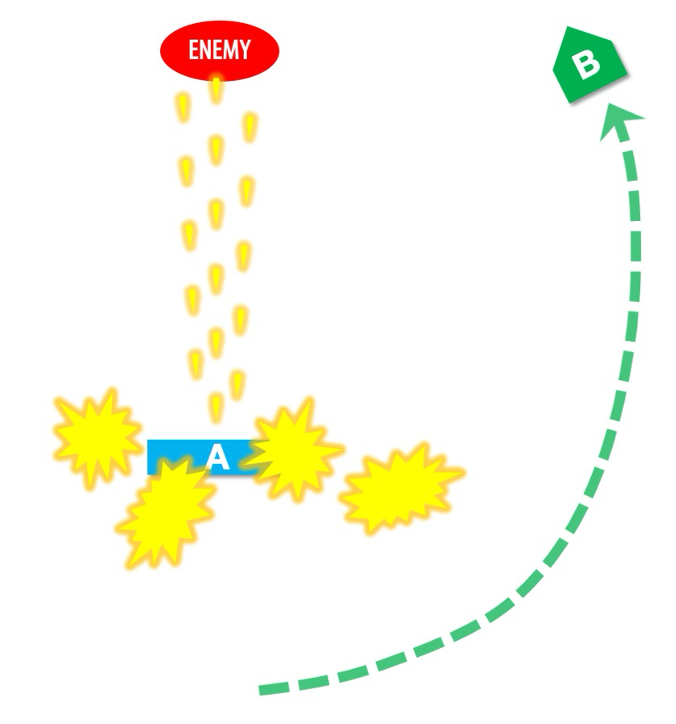

For sake of space, we assume readers are already familiar with the standard “suppress and flank” battle drill. For those who are not, refer to the diagram below. In general terms the suppress and flank battle drill involves one element (A) laying down suppressive fire while a second element (B) moves around to the right or left in a wide, bold flank to attack the enemy unexpectedly from the side.

PROBLEM 1: Engagement Distance and Ammo Load

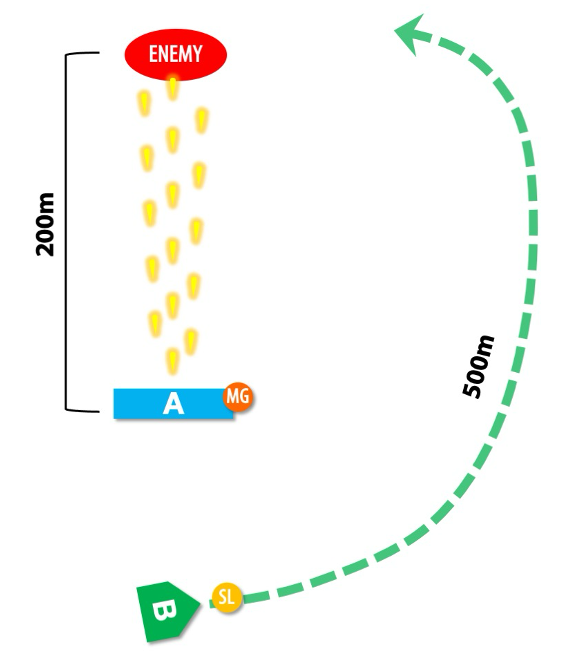

A typical engagement range in conventional warfare could be as far as 200m or 300m. This means if the flanking element makes even a moderately bold flank (as shown in the picture, the total movement distance for the flanking element will likely be farther than 500m. Moving 500m over rough terrain in full gear, especially at night can take time. Then consider that if the machine guns in the support position are firing at a sustained rate of fire, based on standard U.S. Army basic ammo loadouts, the light machine guns will have possibly expended their ammunition and the medium machine guns will likely be at least half-empty by the time the assault element is in position to assault.

PROBLEM 2: Exposure to New Threats and Isolation

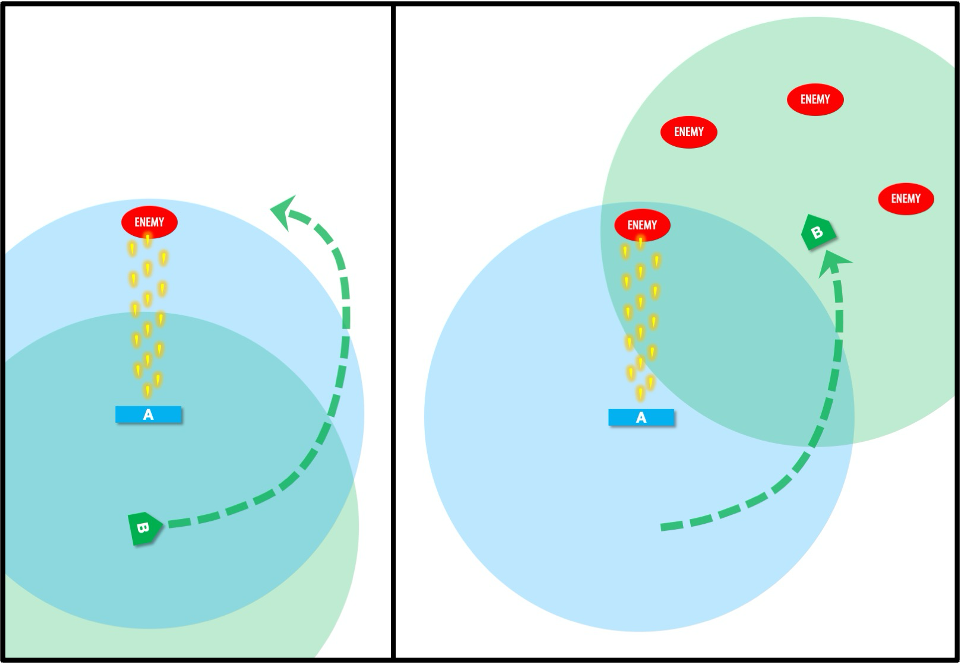

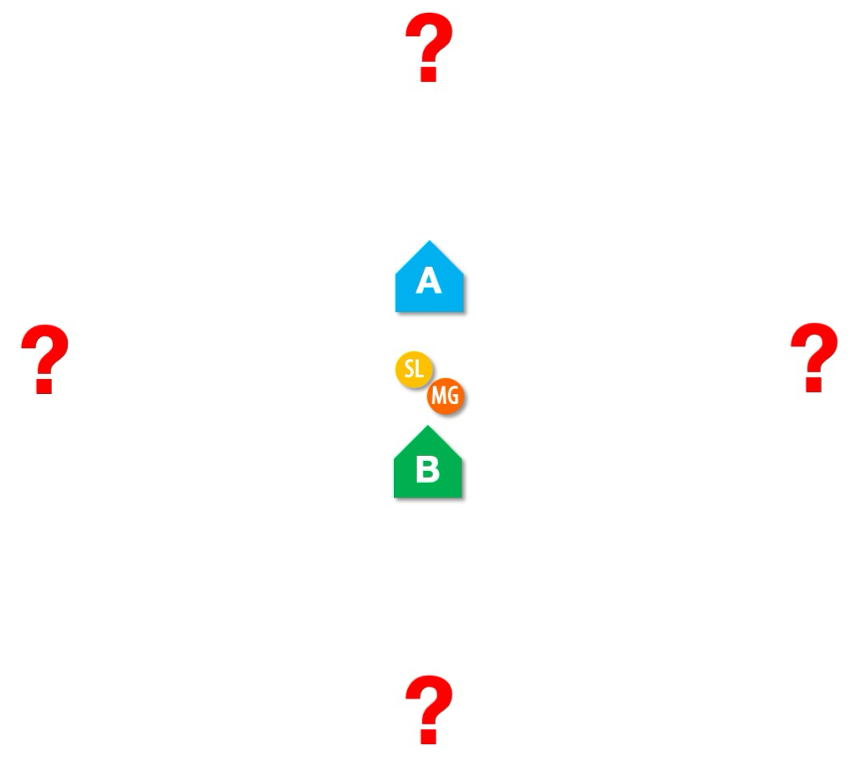

Given the engagement distances just discussed, by the time the flanking element is approaching the assault position, it will be able to see a lot farther and a lot more than the area originally visible to the support element. In the example below with shaded observation areas, the lead team understandably makes contact near the limit of its observation range and will see only one enemy element. As the trail team flanks around and moves ahead, it may see and be exposed to additional enemy elements that are not visible to the support element. The support element therefore cannot provide covering fire to help protect the flanking element from these new threats. This could leave the flanking element completely isolated while facing potentially superior forces.

PROBLEM 3: Unpredictable Enemy Reaction

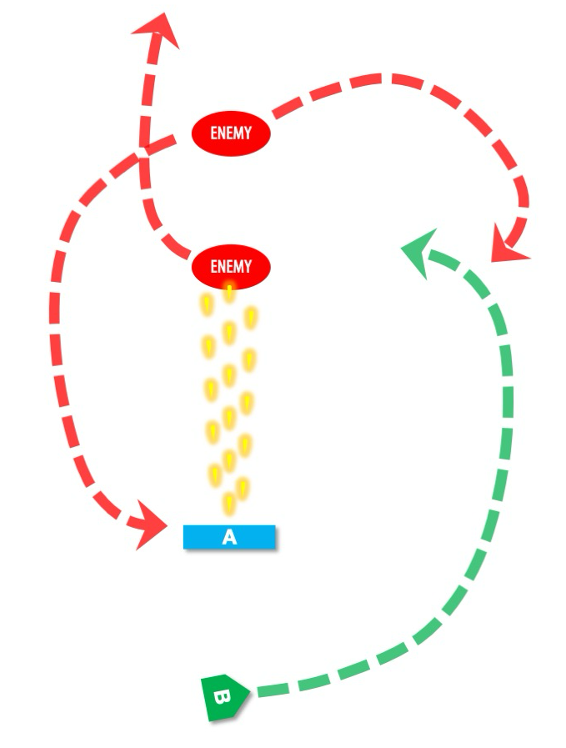

The basic battle drill formula also assumes that the enemy either chooses to do nothing or is unable to do anything because they are completely suppressed by supporting fires. While either of these results is possible, it would be foolish to assume that the enemy will do nothing in every case. Combined with the possibility mentioned earlier of additional enemy units further away that you didn’t initially spot, there are quite a few possibilities for enemy counteraction. The enemy might attempt to flank you from the same side or the opposite side of your flanking element. The enemy might attempt to attack and destroy your support element or anticipate your flank and wait in ambush for your assault element. Even more likely, the enemy will simply try to pull back and break contact. Any of these actions changes the scenario and makes the basic battle drill formula break down in some way.

PROBLEM 4: Enemy Indirect Fire

As already discussed, depending on the engagement range it can take the assault element a while to bound around into the assault position. If the enemy has indirect fire assets like mortars or artillery, he will likely call in a fire mission as soon as the engagement starts. You should study patterns for enemy artillery employment and response time in your area of operations to know the approximate time window you have before rounds start falling on your support-by-fire position. If the enemy response time is fast, it might not be safe or wise to leave a supporting element in place for a long period of time.

PROBLEM 5: Attacks from Other Directions

Battle drills as explained in doctrinal manuals can be applied to enemy contact in any direction. However, because the specific examples, drawings and steps in the manuals often focus on contact to the front, military units frequently end up practicing only attacks to the front and fail to practice executing the battle drill in different directions. While the fundamental steps and movements of the drill remain generally the same, there are some important changes in how you execute the drill based on the direction from which the attack is coming. Taking a more flexible approach to fire and maneuver from the outset sets you up for success when encountering enemies from different directions.

An Alternative to Battle Drills?

We believe that part of the reason why battle drills are misunderstood is because they are expressed as “drills” in the first place. It is difficult to give someone a “drill” but then expect them to deviate from it based on the situation. The spirit of adaptability should be built in to the way doctrine is written, taught and practiced from the start.

We suggest one approach to achieve this goal in our manuals that we call “Battlecraft.” We chose the term battlecraft because the term “craft” suggests a deeper, nuanced and adaptable tactical understanding beyond a rigid drill or process. You can learn more about this approach in upcoming articles.

We hope you found the short article useful and once again we welcome your reactions, comments or suggestions below in the chat area. We want to promote constructive discussions on tactics with people from various tactical backgrounds and experience levels.

Bibliography:

Vandergriff, Donald E. Adopting Mission Command: Developing Leaders for a Superior Command Culture. Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers, 2019.

Vandergriff, Donald E. “An Analysis of ‘The Problem with Traditional “Battle Drills”’.” Substack post. The Warfare Mastery Institute (blog), October 20, 2025.

https://warfaremastery.substack.com/p/vandergriff-analysis-of-the-problem

.

Vandergriff, Donald E. Raising the Bar: Creating and Nurturing Adaptability to Deal with the Changing Face of War. Self-published, 2006.

Vandergriff, Donald E., and William S. Lind. Maneuver Warfare Handbook. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985.

Lind, William S. “Maneuver Warfare Handbook.” In Maneuver Warfare Handbook, by Donald E. Vandergriff and William S. Lind, 1–120. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985.

Warfare Mastery Institute. “The Problem with Traditional ‘Battle Drills’.” Substack post. The Warfare Mastery Institute (blog), October 19, 2025.

.

Warfare Mastery Institute. Small Unit Infantry Rural Combat. Forthcoming serial publication. Substack. The Warfare Mastery Institute (blog), 2025–.

.

CareerFare … a form of new Lawfare.

BTW the “need more data” stall was quite true in the 80s/90s when things were paper.

All computers really did was turn the muzzle loading typewriter into a belt fed automatic weapon that gave bureaucrats unlimited firepower and with email unlimited range.

Have fun with the stable Hercules. 💩 🏭 💩 now virtualized… truly soon we’ll be unable to move… except for AFT tests…

Your analysis is spot on Don. You identify the deeper cultural and organizational causes for the problems we discuss in our article. You are absolutely right that changes at the tactical level will be short-lived without a larger transformation of culture and mindset. We look forward to your thoughts on the next articles on this subject that will go deeper into our concept of “battlecraft.” It won’t spoil the surprise to confirm that it is indeed aligned with 3/4GW, mission command and the principles that you and Bill Lind advocate for. Thank you again for the insightful analysis and we look forward to more of your writing.