Integrating Drones in the Force: The Army Way and the Right Way

While the intent to incorporate offensive drone capabilities is commendable, the approach echoes the same flawed patterns that have plagued Army modernization efforts for decades.

The recent activation of Fox Company, 1-10 Attack Battalion, under the 10th Combat Aviation Brigade of the 10th Mountain Division represents yet another top-down attempt by the U.S. Army to adapt to the realities of modern warfare—specifically, the dominance of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) and launched effects in contemporary conflicts.

Activated on December 16, 2025, at Fort Drum, New York, this “first-of-its-kind” tactical UAS and launched effects company aims to achieve “drone dominance” by integrating reconnaissance drones with the firepower of Apache attack helicopters to hunt and engage enemies in the division’s deep areas.1

While the intent to incorporate offensive drone capabilities is commendable, the approach echoes the same flawed patterns that have plagued Army modernization efforts for decades.

As retired Colonel Doug MacGregor has pointed out in his critique of this initiative, several practical and systemic issues undermine its effectiveness from the outset. First, the 10th Mountain Division, as a light infantry formation, lacks the organic vehicles necessary to transport and sustain the volume of drones required for meaningful operations. Without adequate mobility platforms, the unit’s drones risk becoming static assets or dependent on external logistics that may not be available in contested environments.

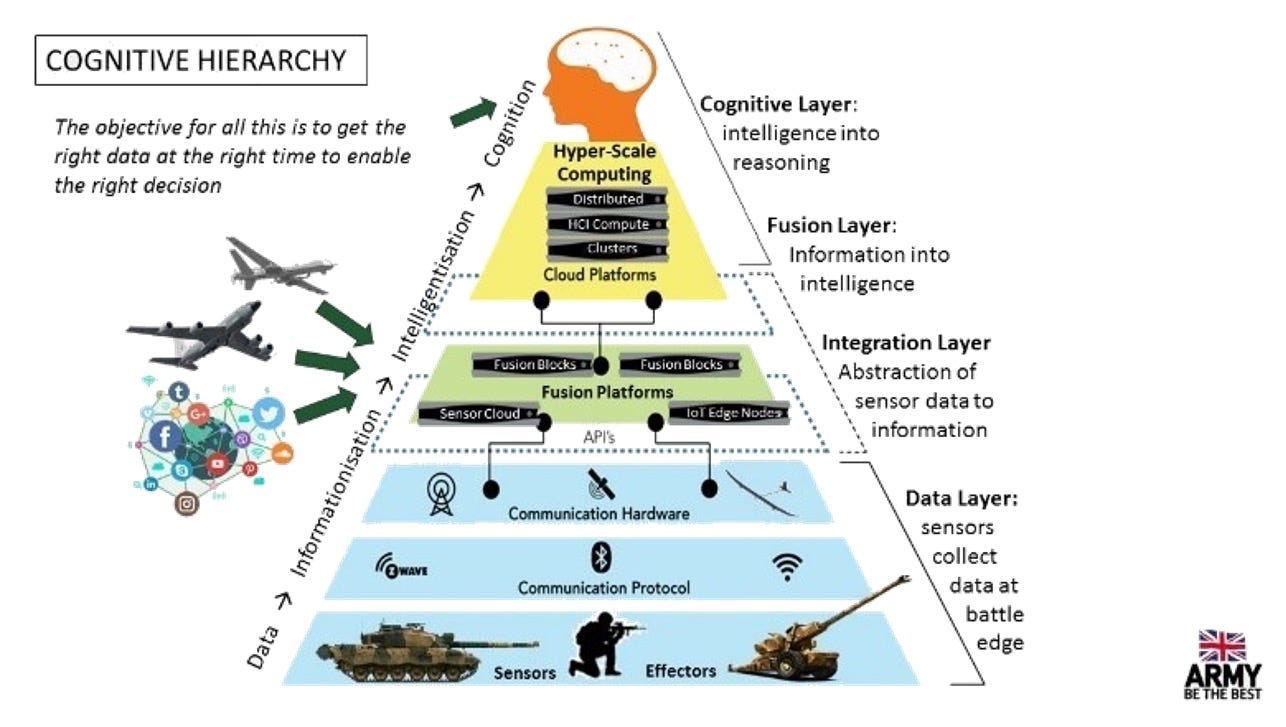

Second, placing this new company under the Combat Aviation Brigade—once again subordinating drone operations to aviation—is a misguided decision. Drones are not merely aerial adjuncts; in 4th Generation Warfare (4GW), they function across domains as sensors, decoys, jammers, and precision strikers, requiring seamless coordination with ground maneuver units, not just rotary-wing assets.

MacGregor’s most damning observation concerns integration with air defense: How will this drone company coordinate with air defense artillery (ADA) units? In a missile engagement zone saturated with unknowns—drones that do not squawk Identification Friend or Foe (IFF)—ADA systems are likely to treat them as threats, wasting precious ammunition in perceived self-defense or, worse, engaging friendly assets.

This is not hypothetical; lessons from Ukraine and other conflicts show that without clear deconfliction protocols, layered air defense and offensive UAS operations quickly devolve into fratricide or neutralized capabilities. The Army’s decision to bolt on a specialized drone company under aviation, rather than embedding drone expertise across all units, ignores these risks and perpetuates stovepiped thinking.2

These shortcomings stem from a deeper, more fundamental problem: the U.S. Army (and much of the U.S. military) remains mired in a 2nd Generation Warfare (2GW) culture. 2GW emphasizes centralized planning, hierarchical decision-making, massed fires, and attrition-based operations—hallmarks of industrial-era warfare. It excels at predictability and scale but struggles against adaptive, decentralized threats.

In contrast, 3rd Generation Warfare (3GW)—maneuver warfare—prioritizes speed, initiative at lower levels, mission-type orders, and rapid adaptation to exploit enemy weaknesses. True mastery of 4GW, however—where irregular forces, hybrid threats, information operations, and low-cost precision weapons like ubiquitous drones blur lines between front and rear—requires evolving beyond even 3GW to a culture that fully embraces decentralization, bottom-up innovation, and resilience in complex, ambiguous environments.

Adding a new drone unit, especially under an aviation headquarters, will not bridge this gap. Drones are tools, not panaceas. Without a cultural shift to 3GW principles that enable the entire force to understand, fight, and win in 4GW, such additions will remain marginal or counterproductive.

The Army needs to empower units at the lowest levels—squads, platoons, companies, and battalions—to experiment organically with drones, tactics, training, leadership (especially decentralized decision-making), and force structure. This means imbuing commanders with the authority and resources to test ideas on their own initiative, then rapidly scaling successful innovations across the force.

This is precisely what the German Army achieved during World War I with the development of Stormtroop Tactics (Stosstrupp tactics). Facing stalemate on the Western Front, the Germans rejected rigid, top-down directives in favor of bottom-up experimentation. Junior leaders—often captains and lieutenants—were given freedom to trial new infiltration techniques, small-unit assaults, combined arms with artillery and machine guns, and flexible command structures.

A dedicated office under Captain Willy Rohr (and later others) captured, refined, and disseminated the best ideas, leading to the publication of doctrinal manuals and widespread adoption. As Dr. Bruce I. Gudmundsson details in his seminal work Storm Troop Tactics: Innovation in the German Army 1914-1918, this process relied on empowering tactical units to innovate, fail fast, learn, and adapt—without micromanagement from higher headquarters. The result was a breakthrough in offensive capability that nearly shattered Allied lines in 1918.3

The U.S. Army could replicate this model today. Allocate modest budgets directly to units for drone procurement, testing, and modification. Reimburse expenses for experiments—whether commercial off-the-shelf drones, custom payloads, or novel tactics—without endless bureaucratic approvals. Encourage after-action reviews focused on lessons rather than blame. Promote leaders who demonstrate initiative and adaptability, not just compliance.

Only through such decentralization can the force develop the doctrinal flexibility, tactical proficiency, and cultural mindset needed to prevail in 4GW, where drones are but one element in a web of decentralized, multi-domain threats.

Until the Army sheds its 2GW culture and embraces a true 3GW evolution capable of mastering 4GW realities, initiatives like the 10th Mountain’s drone company will amount to little more than tinkering at the margins—expensive, isolated, and ultimately ineffective. The time for bold, bottom-up reform is now, before the next conflict exposes these shortcomings on a real battlefield.

Notes:

1 Zita Ballinger Fletcher, “US Army’s 10th Mountain Division Stands Up New Drone Attack Unit,” Military Times, December 29, 2025, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2025/12/29/us-armys-10th-mountain-division-stands-up-new-drone-attack-unit/. The article reports the formal establishment of Fox Company on December 16, 2025, with activation ceremonies occurring shortly thereafter, including on December 18.

2 Doug MacGregor, comment on the 10th Mountain Division’s new drone unit (paraphrased critique emphasizing logistical limitations of light infantry, suboptimal placement under aviation, and air defense coordination risks including IFF challenges and ammunition waste), as referenced in contemporary discussions following the unit’s activation in December 2025.

3 Bruce I. Gudmundsson, Storm Troop Tactics: Innovation in the German Army, 1914-1918 (New York: Praeger, 1989), especially chapters detailing the role of Assault Battalion No. 5 (Rohr) under Captain Willy Rohr, the bottom-up experimental process starting in 1915, training innovations, and dissemination of tactics leading to their influence on 1918 offensives. Gudmundsson emphasizes how tactical units were empowered to improvise and refine infiltration methods, contrasting with more centralized approaches elsewhere.

4 Samuel Bendett et al., “The Russia-Ukraine Drone War: Innovation on the Frontlines and Beyond,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), May 29, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-ukraine-drone-war-innovation-frontlines-and-beyond. This analysis highlights widespread tactical EW (”trench-level warfare”) and fiber-optic adaptations to counter jamming, noting that lack of communication leads to high drone fratricide rates on both sides.

5 U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), “Ukrainian Unmanned Aerial System Tactics,” March 18, 2025, https://oe.tradoc.army.mil/product/ukrainian-unmanned-aerial-system-tactics/. The report details swarming tactics, counter-UAS evolution (including jamming and nets), and the need for improved coordination to avoid fratricide in layered defenses.

6 Tsiporah Fried, “The Impact of Drones on the Battlefield: Lessons of the Russia-Ukraine War from a French Perspective,” Hudson Institute, 2025, https://www.hudson.org/missile-defense/impact-drones-battlefield-lessons-russian-ukraine-war-french-perspective-tsiporah-fried. Emphasizes that traditional air defense was not designed for mass drone swarms, requiring improvised layered strategies including deconfliction at machine speed via AI-assisted C2.

7 Institute for the Study of War (ISW), “Russian Drone Innovations are Likely Achieving Effects of Battlefield Air Interdiction in Ukraine,” September 2, 2025, https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russian-drone-innovations-are-likely-achieving-effects-of-battlefield-air-interdiction-in-ukraine/. Details Russian adaptations like mothership UAVs and fiber-optic FPVs for rear-area interdiction, contrasting with Ukraine’s rapid scaling of low-cost systems.

“Drones are tools, not panaceas.”

bingo! and even monkeys use tools. some are not as smart as monkeys because they like to admire complexity and complication over simplicity. 💋

2nd Brigade, 25th ID, one of the TiC 1.0 formations, is and has been integrating drones down to the squad level. I would assume 10th Mountain and 101st have been as well with their TiC Brigades, and that this formation attached the aviation unit is in addition to, and not in lieu of, tactical UAS deployed in line formations.

Further, IBCT’s are in the process of acquiring tactical mobility through conversion to MBCTs, which should mitigate some of the mobility concerns (which to be frank, were and are not limited to UAS employment).

With the Army deactivating cavalry squadrons, a certain amount of centralized reconnaissance will be needed at the brigade and division level to replace them. I also think over the next few years the Army will be figuring out how to handle the disruption zone fight with their SBCTs and ABCTs under the new force structure.